CUARZO: Cities, Urban Planning and Architecture in the reconstruction of the 0 Zones

The creation of the first Japanese cities, the recovery after World War II and the reconstruction of northern cities after the tsunami of 2011.

Author

Andrea González1

1 Spatial Transformation Laboratory (STL), Institute for Spatial and Landscape Development (IRL), ETH Zürich, Stefano-Franscini-Platz 5, 8093 Zürich, Switzerland

Summary

A follow-up on the historical development of the cities of Japan and their periodical destruction and reconstruction since the country’s first settlements, a pattern on how Japanese cities are periodically built and un-built can be studied in order to further examine the “temporariness” of spatial development in its territories throughout history.

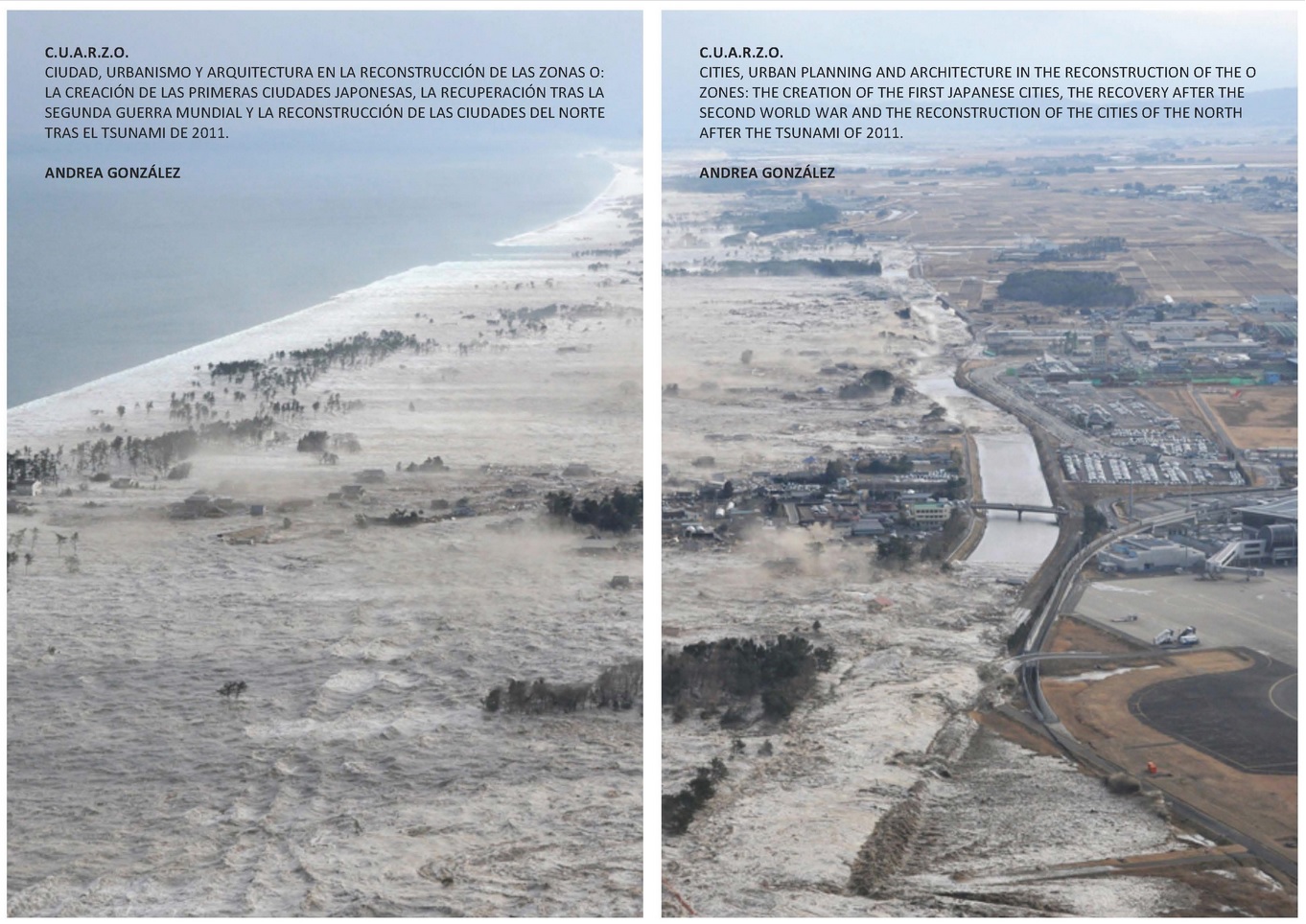

On March 11, 2011, the Great East Japan Tsunami caused one of Japan's worst tragedies since World War II leaving around 16,000 people dead and 2,500 missing. Today, nearly ten years after the tragedy, many cities and villages in Japan are still trying to recall how their urban environment looked just a few decades ago. These thoughts are recurrent in the history of Japanese urban planning since the country’s society transversally accepts cities’ destruction and reconstruction as a natural characteristic of their land and lives with the concept of “temporariness” in its spatial planning since the beginning of its history.

The project and book “CUARZO: Cities, Urban Planning and Architecture in the reconstruction of the 0 Zones” proposes the following questions concerning this situation: Can architecture and urban planning explain a concrete pattern in what we could call “temporary cities?” What does the concept of “temporary” mean in Japan for philosophers, designers and planners? Are there any relevant times throughout history in which these patterns were especially clear regardless of the kind of destruction they went through? Is there a vision for the coastal regions – usually more affected by tsunamis due to their geographic location that helps develop and foresee the future un-planning and re-planning of these regions? What have we learned in these ten years since the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011? The project aims to understand the development and patterns of urban poles of Japan throughout three concrete moments in history in which several cities, villages and interurban spaces were erased from the map due to human-triggered causes, armed conflicts or natural disasters.

Abstract

The research is organised along three axes: The creation of the first Japanese cities, the recovery after World War II and the reconstruction of the cities of northern Honshu after the Great East Japan Tsunami of 2011.

The first analysis explains the problems of the early Japanese settlements that later became cities from an architectural and urban planning point of view. The temporariness of the first Japanese capital cities is studied in the first chapters of the book such as that of the Nara, the Kamakura and Muromachi periods. Through this research various urban typologies can be deployed and several examples unveiled such as the castle-cities, the fortified cities or the port-cities, including their interurban-spaces such as the Tokaido and examples of the rise and fall of the biggest historical urban poles such as Osaka and Edo.

The second analysis explains the perspective of temporariness from an architectural and urban planning point of view. In the middle ages the traditional Heian period architectural construction style, known as Shoin, was adapted after a long period of wars and transformed into the Shoin and Sukiya styles which had more flexible floorplans and provided a higher elasticity of space. Both systems were established after several internal conflict periods that led to an overall destruction of the previous cities and to a shift in traditional constructions that became more ephemeral spaces. The Minka or traditional countryside constructions as well as the Machiya or city constructions reflected this trend too, in which new more flexible construction systems were implemented. During the Muromachi and Kamakura periods, the Machiya architecture also started to transform the urban plan of the city by densifying the space in between the houses in order to protect themselves from wars and exposing them, at the same time, to a higher risk of fire devastation.

The history following the Tokugawa Shogunate led to four fundamental changes in the architecture and urban planning in the 19th and 20th centuries: The Meiji era, the Taisho era, the Showa era and the Heisei era. Through these periods, most of the country’s urban settlements were recurrently exposed to a built – unbuilt pattern due to natural disasters, armed conflicts or human-caused disasters. The devastation and ensuing reconstruction of the cities during and after World War II constitutes the most important part of this axis. In this section, the old patterns of former cities and the time span in between the newly-built cities are studied. The result is a temporary, morphological and sociological analysis that takes into account a number of temporariness- triggering events such as the 1923 earthquake, for example.

The third axis of the research project depicts the reconstruction of the cities of northern Honshu after the Great East Japan Tsunami of 2011. The 2011 Japan earthquake, also known as the Tohoku Chicho Taiheiyo-Oki Jishin, was a magnitude 9.0 Mw earthquake that occurred on March 11th, 2011. Its epicentre was located 130 kilometers from the city of Sendai and generated a large tsunami that devastated parts of the provinces of the cities of Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima in the northern part of Japan, also known as Tohoku. This coastline is located in a high-risk area and frequent earthquakes and tsunamis have been historically known to occur along it and have caused the destruction of coastal towns and villages facing the Pacific Ocean since ancient times. For example, in 1933 a large tsunami known as the Showa Tsunami destroyed approximately the same area as the one devastated in 2011. The gravity of this situation became even greater after the March 2011 event as the tsunami generated by the earthquake reached the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant causing the meltdown of reactor number III and generating a nuclear panic in the country and the world, only matched by the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986. According to the Japanese National Police Agency, the earthquake and tsunami caused property damage amounting to 10,000,000,000 dollars, and 45,700 buildings were destroyed, while 144,000 constructions were damaged and some 25,000,000 tons of debris were generated.

This part of the research project studies several urban and architectural strategies that these territories followed in between 2011 and 2021. Derived from the author’s experience in the field, spending nearly two years participating as a volunteer in the reconstruction of the cities around Fukushima, a detailed urbanistic and sociological study is conducted, examining temporary villages like Onagawa, provisory infrastructures, like the green barriers, the inter-urban temporary settlements and the ready-to-be-dismantled constructions and ephemeral sacred spaces.

The temporary urban poles recurrently located in conflict areas create new dichotomies related to permanent and temporary settlements giving form to a new approach to understanding spatial planning in a more resilient, regenerative and more humble way. The short-term reconstruction after the 2011 Great East Japan Tsunami has shown how cities return to life after death.

This study, published just before the 10th anniversary of the 2011 tsunami, aims to better understand historical and contemporary territorial strategies as well as the boundaries of temporary urban planning in the country.

Selected Literature

Collcut, M., Jansen, M., World Cultural Atlas. Japan. Ed. Del Prado. Folio Vol I pp. 40

González, A. (2013): Japan, two years after the tsunami. In: Arquitectura Viva, Architecture Press, Vol. 151, p. 53-56. 04, 2013 (ISSN: 0214-1256)

González, A. (2013): Interview with reconstruction Project coordinator in Tohoku, Japan: Mikio Yamaguchi. In: Panorama, Architecture Press, Vol. 4, p. 2-5. 04/2013 (ISSN: 1885-8228)

González A. (2016), JADE. Tokyo 1991-2011, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. pp. 156–170.

González A. (2020), CUARZO: Cities, Urban Planning and Architecture in the reconstruction of the 0 Zones: The creation of the first Japanese cities, the recovery after the second world war and the reconstruction of the cities of the north after the tsunami of 2011. Ed. Metropoly (2020) pp. 1-20

Hidemasa, Y. (2013) To What extent is a Disaster Assumed in Architectural Planning and Design en Journal of Architecture and Building Science vol. 126 N. 1623 pp.40-41

Isozaki, A. (2011) Poem Destruction of the Prototype: The Incubation Process in Koolhaas Rem and Ulrich Obrist Hans Project Japan Metabolism Talks Ed.Taschen (Köln) pp. 38

Kazuo, S., Hamada, M., Kuwata, T., Mori, T., (2011) Fishing village Planning for the Tsunamis e Investigative research upon the Damages to Houses caused by Sanriku-Tsunamion the 3rd March 1933 Designing Nation, People, and Land: Vol I I-Tohoku as Archives. Journal of Architecture and Building Science 2011-11 vol 126 n. 1624 pp.2-3

Kitahara, I. (2012) Let us Resuscitate Lessons of Tsunami Epigraph en Designing Nation, People, and Land: Vol I I-Tohoku as Archives. Journal of Architecture and Building Science 2011-11 vol 126 n. 1624 pp. 34-35

Kojiro, K., (2011) Tohoku Analysis 1960 Designing Nation, People, and Land: Vol I I-Tohoku as Archives. Journal of Architecture and Building Science 2011-11 vol 126 n. 1624 pp.4

Masuda, T., Futagawa, Y., (1971) Universal Architecture Japan Ed. Garriga. SA Barcelona pp.35

Nakajima, N., (2012) Archiving Planning Heritages Vision from the History of Restoration Plan in Sanriku Area en Designing Nation, People, and Land: Vol I I-Tohoku as Archives. Journal of Architecture and Building Science 2011-11 vol 126 n. 1624 pp. 26

Nomura, R., (2012) Relocation across the Channel and the Current life of Evacuees en Great East Japan Earhtquake series. Serial Report 2. Life in temporary housing.n1. Journal of Architecture and Building Science vol 127 n. 1626 pp.10

Sorensen, A. (1955) Japan´s first urban planning system Nissan Institute /Routledge Japanese Studies Series www.books.google.es pp.114

Shinji, T. (2012) Constructing Temporary Houses at the Great East Japan Earthquake Journal of Architecture and Building Science 2011-10 vol. 126 N. 1623 pp. 49

Shigeo, T. (2013) Dispersed Living in Private Apartments. A new form of temporary living Great East Japan Earthquake. Serial Report 2. Life in temporary housing. N.12 en Journal of Architecture and Building Science vol. 127 N. 1639 2012.12 pp. 2-3

Tange, K., Gropius, W., Ishimoto, Y., Katsura (1960) Tradition and Creation in Japanese Architecture Ed. Yale University Press pp. 33

Whitney H. J., (1973) Universal History of the Japanese Empire Universal del siglo XXI Ed. Siglo XXI de España Editores SA pp. 17